In Hindu mythology, Lord Brahma is

revered as the creator of the universe and one of the Trimurti, the holy

trinity that includes Vishnu the preserver and Shiva the destroyer. Brahma is often

depicted with four faces, each representing one of the four Vedas the ancient

scriptures of Hindu philosophy and spirituality. His multi-faced appearance

symbolizes his ability to see in all directions and comprehend the vastness of

creation.

Brahma's role in the cosmic cycle is

pivotal. According to Hindu cosmology, he is responsible for the creation of

the world and all living beings. He is believed to have emerged from the cosmic

ocean at the beginning of time and created the universe through his divine

thought and will. His consort, Saraswati, the goddess of wisdom, art, and

learning, complements his creative energy. Together, they symbolize the balance

of knowledge and creativity in the universe.

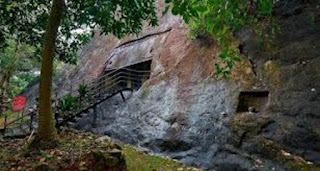

Despite his importance, Brahma's

worship is less common than that of Vishnu and Shiva. There are few temples

dedicated solely to him, with the most notable being the Brahma Temple in

Pushkar, Rajasthan. This temple is unique, as it is one of the very few places

where Brahma is actively worshipped.

In Hindu philosophy, Brahma

represents not only the physical creation but also the manifestation of the

universe's potential and consciousness. He embodies the principle of Rajas

(passion), which is essential for creation, contrasting with Vishnu's Sattva

(goodness) and Shiva's Tamas (darkness).

Brahma's character also serves as a

reminder of the impermanence of life and creation. In various texts, it is said

that he undergoes cycles of creation and dissolution, paralleling the life

cycles experienced by all beings. Thus, Brahma's narrative underscores the

cyclical nature of existence in Hindu cosmology.

In summary, Lord

Brahma is a central figure in Hinduism, representing the creative force

of the universe. While not as widely worshipped as his counterparts, his

significance as the creator continues to resonate in spiritual and

philosophical discourses.